Food for the Soul: Pink

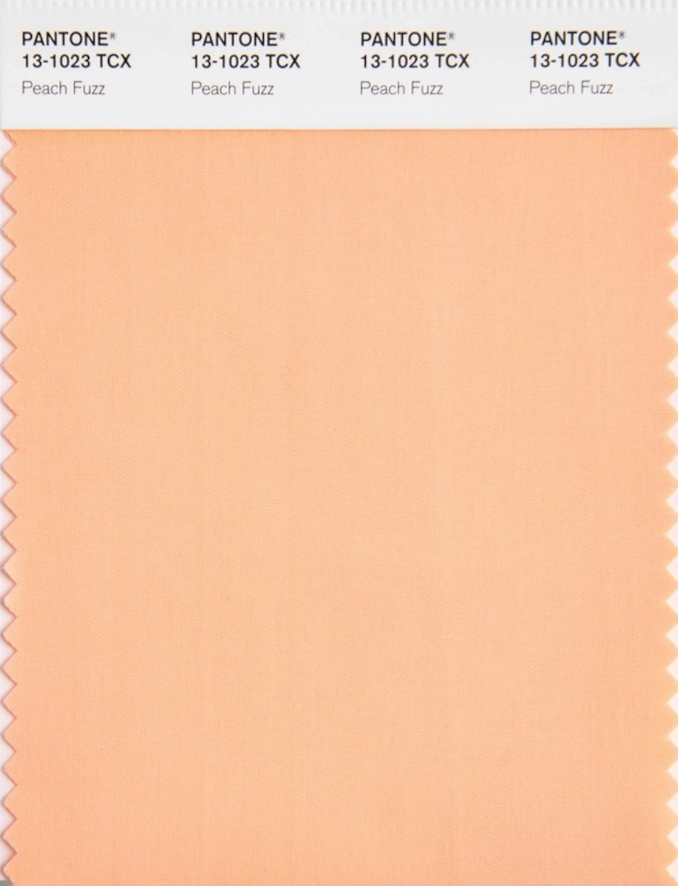

For its Color of the Year 2024, Pantone elected the color named “peach fuzz”—a pink color moderated by some orange or yellow to achieve a shade that in clothing can indeed be called “peach,” while in art it is often used to render skin tones, the light at dusk, or morning clouds in southern latitudes.

So Pantone’s “peach fuzz” pink of the year is the shade with which we can start looking at the color pink in art.

NUDE PINKS

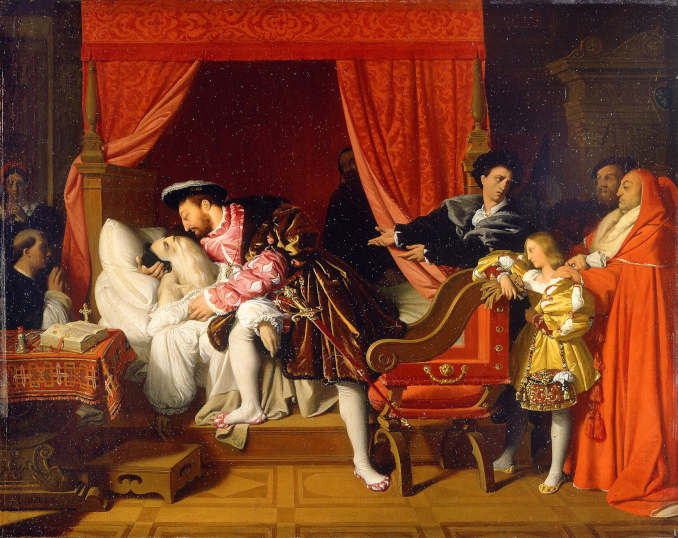

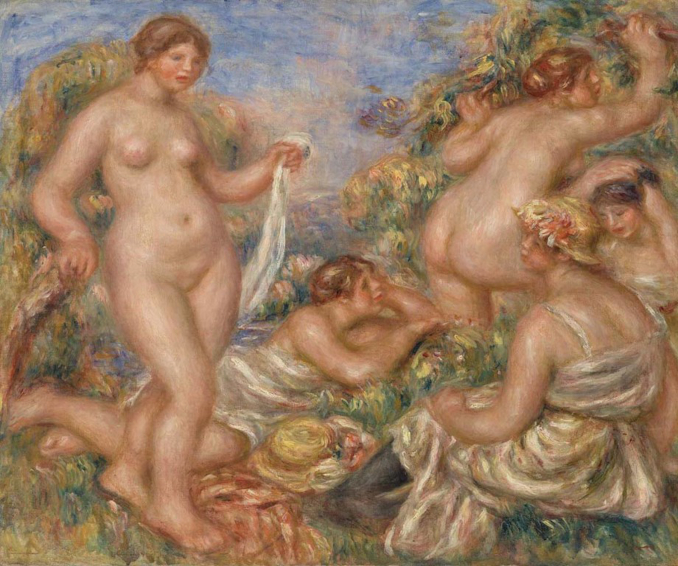

Innumerable painters, from masters to students and from the Renaissance until now, have produced ever popular paintings of nudes. There is a long line of masters of beautiful flesh, stretching from Botticelli, Raphael, and Titian through Rubens and Ingres and ending with Renoir. Afterwards, art went into Modernism’s preoccupation with color, line, or style but not necessarily focusing on realistically depicting women’s beauty. For Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919), an avowed admirer of women, beauty was paramount. “Nothing better will ever be invented than a naked woman (whether she is emerging from sea bed or her bed, and whether her name is Venus or Nini),” he would say.

Renoir took up painting nudes—though he mostly called them “bathers,” a nice term to pacify moralistic gallery visitors—in the second part of his life, when his Impressionist fights, struggles with poverty, and creation of iconic landscapes and portraits were behind him. He moved on to painting children—one of his favorite subjects—and to creating compositions with young models blessed with luminous skin tones. His Composition, Five Bathers is one of his last paintings, made at a time when arthritis and pain from an infected foot limited his mobility. In his last ten years he lived near Nice, in the small town of Cagnes-sur Mer, situated on a bucolic hillside above the Bay of Angels. There, in the evenings, the sky can turn exactly this type of peachy pink while the shade of olive trees throws dappled light onto everything. This luminous pinkish tint that you can spot in the sky is used here by Renoir to color the sinuous forms of the bathers.

The south of France is not the only place where the evening skies can be streaked with such peachy colors. In many places on the Mediterranean coast and around the Adriatic, the sunsets have the same impossible palette of pinks, violets, and salmon oranges. No one captured that sky better than Giambattista Tiepolo (1696-1770), the master of ceilings that he frescoed in his native Venice, at a German principality, and at the Royal Palace in Madrid.

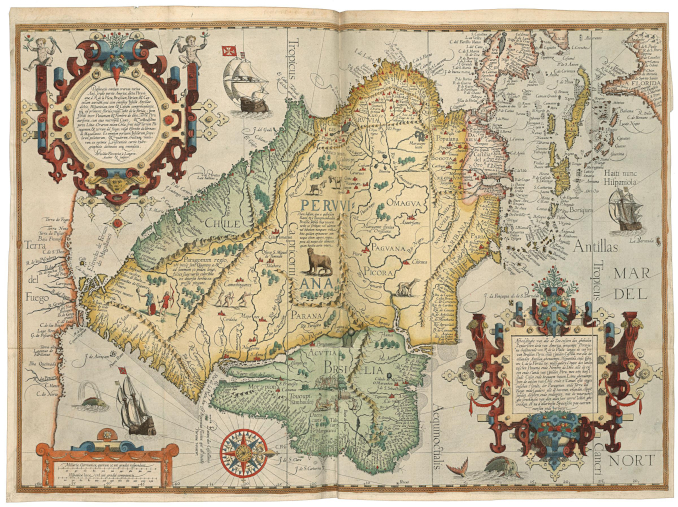

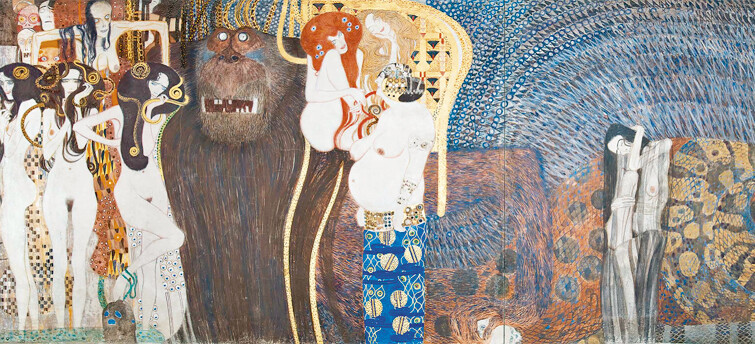

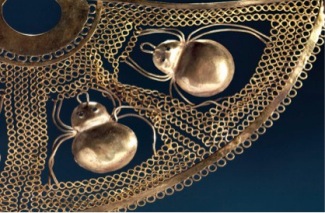

The decoration that he painted for the residence of the Prince-Bishop von Greiffenclau in Würzburg is the largest fresco in the world, measuring 100 x 62 ft (19 x 30,5m). It is titled Apollo and the Four Continents, featuring allegories of the four parts of the world known at the time. America, shown in the image above, is presented as a scary wilderness because in the mid-18th century, most Europeans had a very vague idea of this “savage land” across the Atlantic Ocean. The central figure is an allegory of America—a Native woman, festooned with feathers, astride a giant crocodile and surrounded by fierce-looking warriors. The sky above those outlandish figures is hardly an American one though; Tiepolo painted what he knew best—a swirl of pinks, yellows, and violets from the gentle skies over his native Adriatic.

PALE PINKS and PEACHY HUES

The palest of pinks is the leading color in the composition with a very long title: Symphony in Flesh Colour and Pink: Portrait of Mrs. Frances Leyland. James Abbott McNeill Whistler (1834-1903) painted various monochromatic portraits, such as a picture of his own mother using black, grey, and white and a famous picture of a girl all in shades of greenish gray and white. This picture, however, is all about the ethereal light pink. The model is the wife of shipowner Frederick Leyland, an art collector and Whistler’s patron, for whom Whistler decorated a dining room in Leyland’s Kensington mansion—the famous Peacock Room. That magnificent interior design became a cause of a protracted conflict between artist and patron. Leyland and Whistler had a falling out, Whistler went bankrupt, the magnate bought up his debts to exert some control over the artist, Whistler took revenge in the form of a satirical painting, the architect who designed the room ended up in an asylum, and Frances Leyland eventually left her husband. And it all started with the ill-fated house design project.

If you simply like pretty compositions of flowers in a vase, Henri-Fantin Latour (1836-1904) is for you. He was so good at painting bouquets of flowers, usually roses and peonies with fluffy pink petals, that he never lacked for commissions, churning out those compositions one after another—most of them exquisitely done in a style reminiscent of the Dutch Baroque, but with a fresh, bright palette and the French lightness of touch. The funny thing is that Fantin-Latour was a friend and contemporary of Whistler, Manet, and Courbet, but his art was steeped in the visual traditions of earlier eras, entirely ignoring the new styles of Impressionism or Modernism.

No examination of portraits of beautiful women in gorgeous pink silks can take place without looking at the art of John Singer Sargent, that master of elegant fin-de siècle portraiture. Mrs. Carl Meyer and her Children features the beautiful peachy pinks of the taffeta dresses of a socialite. The sitter was the wife of a banker and co-chairman of the De Beers diamond company. She could afford both the best pink silks and the most fashionable portraitist available, and presumably she was satisfied with this impressive family portrait. However, Sargent’s composition was less appreciated by art critics, who ridiculed this painting. A reviewer objected to the vertical perspective, lampooning the composition in Punch (London’s satirical magazine) as a “sort of drawing-room toboganning exercise.” This painting was painted in 1896; in a few short years, art would be full of daring compositions by Picasso, Kandinsky, Braque, and Malevich, and no amount of press criticism would stop Modernism from upending traditional ideas about how to correctly paint people.

Speaking of Sargent’s pinks, take a look above at his masterpiece called Carnation, Lily, Lily Rose (the title comes from a song)—a study of the light at dusk. He painted this picture over two summers, in 10-minute increments, capturing the glow of fading light during the transition from daylight to darkness. His models (children of his friend) would be posed with props, and he would scramble up a scaffolding with his paints and brushes, painting as much as he could during those few minutes when candlelight would cast a pinkish glow at everything around: the children’s clothes and faces, and the white lilies above them. He painted a portrait of the magic of a summer evening when the light is gentle and the air is perfumed with the scent of flowers and grass.

DUSTY ROSES and AMARANTHS

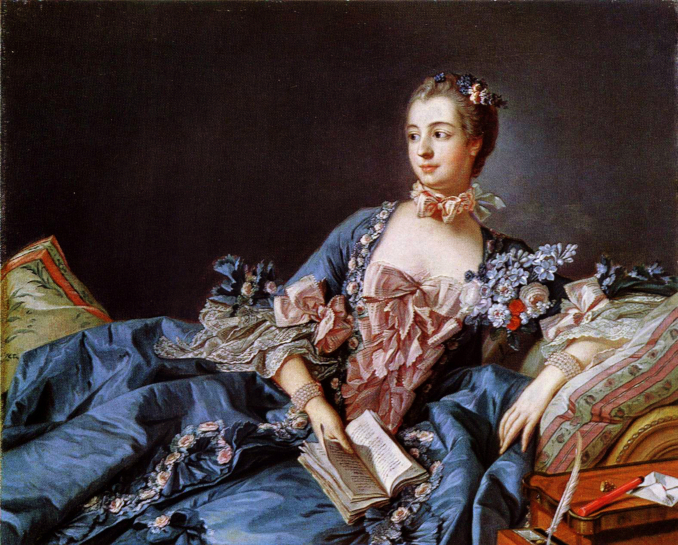

Thanks to French artists such as Boucher (1703-1770) and Fragonard (1732-1806), the Rococo style is all about pastel pinks and baby blues. Boucher painted innumerable images using all shades of pink—skin-colored peach pink for the bodies of cherubs and goddesses, darker pinks for diaphanous cover-ups of nymphs, and dark pink for bows and roses adorning court ladies. He used the darkest cherry pinks for the make-up and clothing of his famous patroness, Madame Pompadour, whom he portrayed several times and who was said to be very fond of this dark pink color. Here is one of her best portraits by Boucher. She is holding a book to signal the learning and intellectual wit for which she was famed, but clearly her intellectual prowess did not stop her from enjoying a beautiful dress adorned with a cascade of purplish-pink bows.

From our perspective of 200 years later, Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun (1755-1842), a portraitist who started her career in France just before the revolution, is one of the most important artists of the transition period between Rococo and Romanticism. But she did not start that way. When she was young, she struggled as a female artist until she had both the fortune and misfortune to befriend Marie Antoinette, Queen of France. Thanks to her royal patroness, Elisabeth became a sought-after court portraitist, but when the winds of history swept the queen off the throne they sent the painter into a long exile, which she spent mainly in Russia. Le Brun’s Self-Portrait with a Straw Hat belongs to happier times when, together with her royal patroness, she was in the forefront of setting out the new fashion of muslin gowns, straw hats, windswept hair, and the style of romantic-looking “shepherdesses.” She also knew that this dusty-rose shade of pink would bring out the youthful complexion of her skin and contrast well with the blue-grey of the sky behind her. This picture was Le Brun’s calling card for potential clients—“Look how well I can paint a woman’s portrait!” she seems to say. And she did—she painted about 600 portraits in her long life.

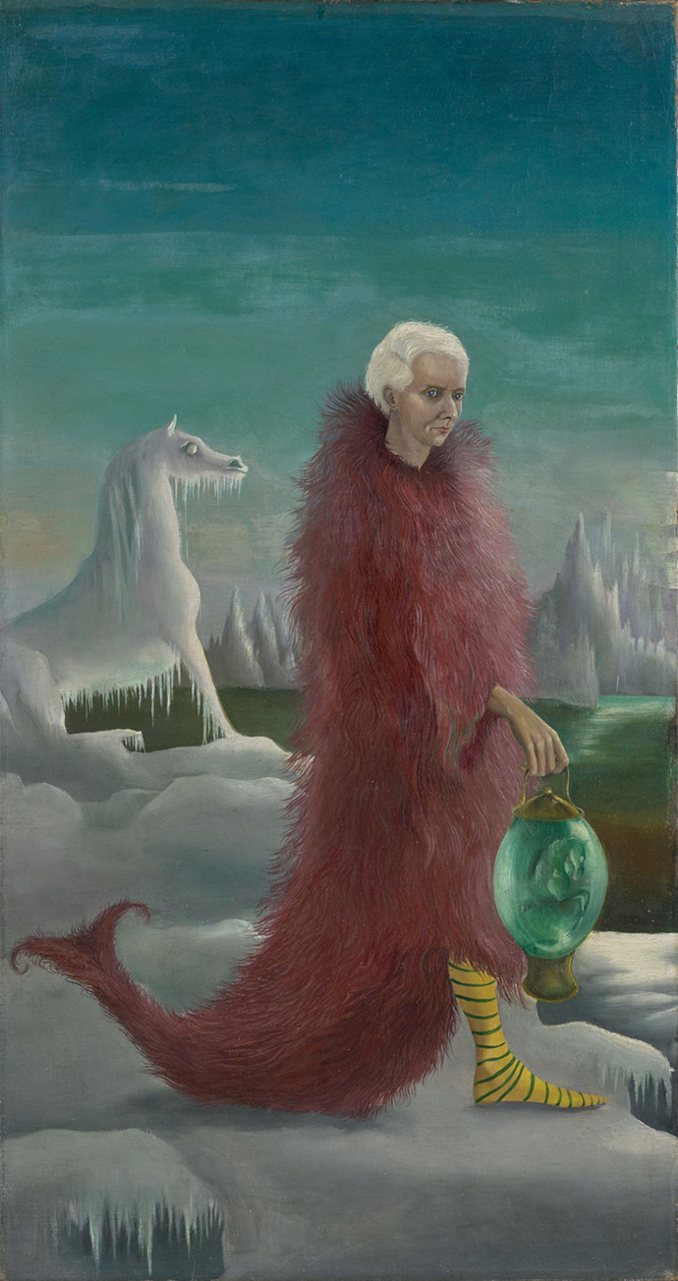

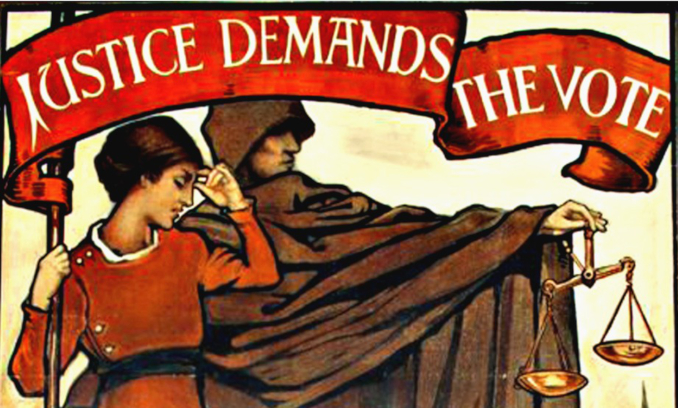

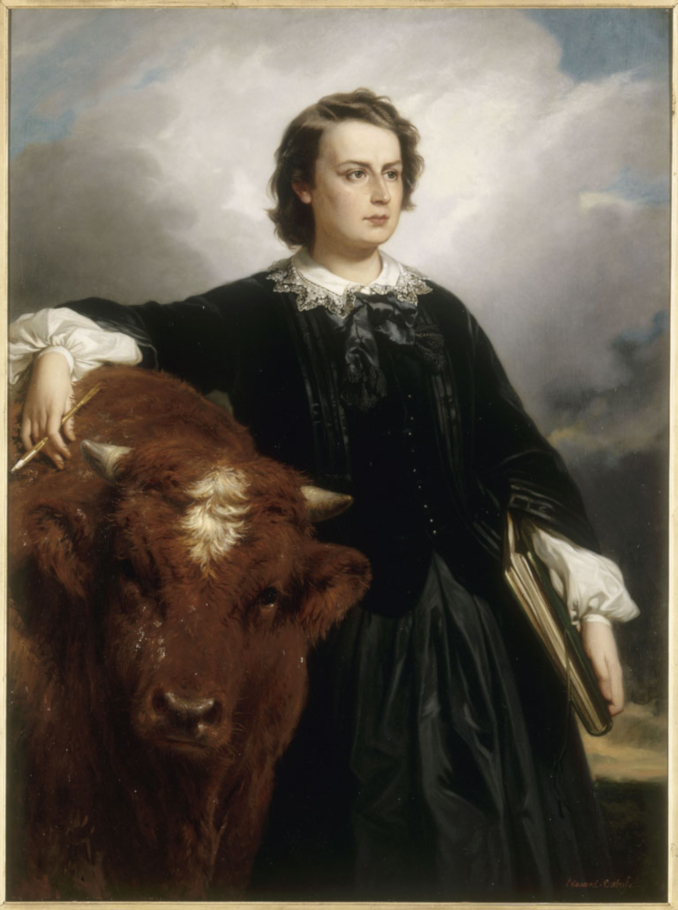

Evelyn De Morgan (1855-1919) painted Night and Sleep almost exactly 100 years after Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun created her self-portrait, but the two pictures share a graceful fluidity of lines and the love of darker shades of pink. De Morgan was one of the few professionally trained female artists in the circle of the Pre-Raphaelites, an English movement that embraced symbolic and mythological imagery while rejecting Victorian realism. A rejection of conventions was a hallmark of Evelyn’s biography. She started out by rebelling against her mother’s wishes to have “a daughter, not an artist,” enrolling in professional art school at age 17. Later, she further rejected her upper-class family’s expectations by marrying a much older man and an artist. She also spent many years supporting social causes such women’s suffrage and pacifism. In art, De Morgan created her own style of symbolic imagery, mostly of female figures, sometimes painted in the newly created bright colors of synthetic pigments. In Night and Sleep, the figure of Night is swathed in amaranth pink. Her son Sleep, is floating alongside, scattering poppy flowers as he flies over earth. Poppies were the source of laudanum, the Victorian sleeping drug of choice. The amaranth gown of Night is matched by the pink hue of the poppies.

Thomas Eakins (1844-1916) was a contemporary of Evelyn De Morgan, but artistically he had nothing in common with her Symbolism or Aestheticism. He used photography to achieve greater realism of human movement, his art courses included anatomy lessons and life drawing (also offered to female students, which got him fired from the academy), and he used camera obscura to achieve veracity of proportions in his paintings. His portraits, including his masterpiece group portrait called The Gross Clinic, aimed at naturalism of image and a psychological truth about the people portrayed. His search for the truth about his subjects is quite evident in his portraits of women, including this picture of a young woman in a rose-colored dress. Painted in the manner of Baroque paintings, she is set against a dramatic black background and lit by one “off-screen” source of light, which highlights her youthful complexion and accentuates the hue of her dress. Maud Cook once gave an interview about this painting: “As I was just a young girl my hair is done low in the neck and tied with a ribbon. Mr. Eakins never gave the painting a name but said to himself it was like ‘a big rosebud.’’” Indeed, the pink of her dress is a way for the artist to describe the pinky glow of innocent youth.

FUCHSIA

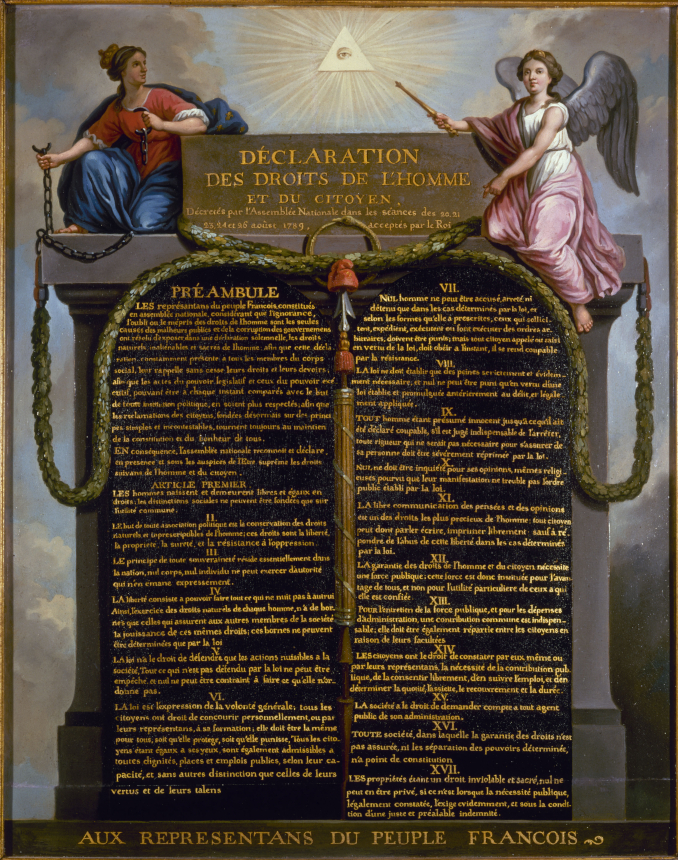

Fuchsia is a shade of hot pink named after Leonhard Fuchs, a German physician and herbalist who published in 1542 a compendium of plants, including many exotic ones from the newly discovered continent. He is the one who gave foxgloves the evocative name of digitalis purpurea (which means “purple fingers”). The plant with vivid pink flowers that we know as fuchsia was not discovered by Europeans until 1703—the explorer who first found it named it fuchsia in honor of the Renaissance scientist. Fuchsia is the shade that was evidently a popular choice for ballerina costumes in 19th-century Paris because Edgar Degas (1834-1917)—the artist whose fascination with ballet, opera, and stage had no bounds—painted many ballerinas in bright fuchsia tutus.

The majority of Degas’s ballerina pictures are created in interiors—at rehearsal halls, on stage, or backstage. Ballerinas in Pink is unusual because the dancers are grouped in front of some greenery—perhaps deliberately posed outside or maybe spotted during a rehearsal break at the back entrance of the dance hall. Regardless of the circumstances, the bright greenery contrasts vividly with the fuchsia tones of the tutus. Ballet tutus are made of tulle fabric that is stiff but can be fluffed up, and the artist has rendered them in energetic slashes of graduated color. The ballerinas’ faces are in the shadow or slightly obscured, so our eyes are drawn to those slashes of outrageous pink against the green.

By 1880 when Degas made this pastel, his eyesight was failing, and he moved from painting oils to drawing in pastels and making sculptures. For the same reason, he also favored bright, contrasting colors—what better hues to choose than a palette of orange and pink for the curtain, and pink and blue for the dancers’ skirts? The coloring is garish and a bit hard on the eyes, but the viewpoint is masterly. We have a birds-eye view of a line dance choreography; everything is in movement—the dancers’ lines are swirling, the violin bows are going up, and all the while, the curtain is going down. All this Degas drew using a few chalky sticks of fuchsia-pink and orange.

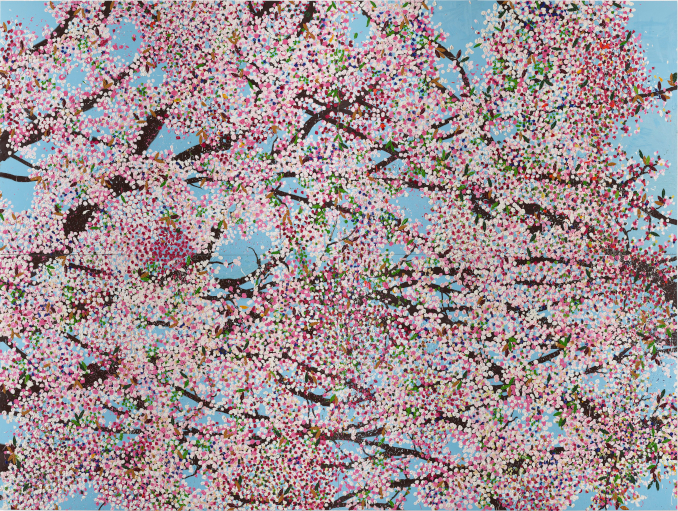

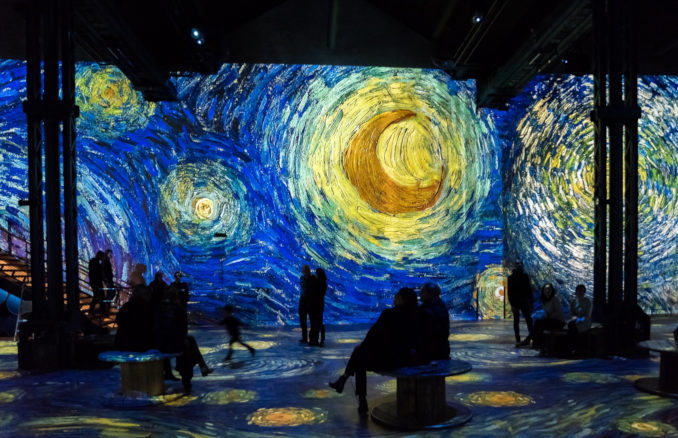

In the art of previous centuries, the color pink had obvious uses for painting flowers, dresses, and sunsets. Since the 20th century, pink can show up in any images: in Andy Warhol’s pop-art of Marilyn Monroe, as Christo’s pink-plastic-swathed Florida islands, or in Murakami’s manga characters painted in fluorescent acrylics. There are no limits for the pink hues in art.